Thierry Ollivier

Thierry Ollivier

A ground-breaking international loan exhibition devoted to the Hindu-Buddhist art of first- millennium Southeast Asia goes on view at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art today.

Some 160 sculptures are featured, many of them large-scale stone sculptures, terracottas and bronzes. They include a significant number of designated national treasures lent by the governments of Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Myanmar, as well as stellar loans from France, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Thierry Ollivier

Thierry Ollivier

The exhibition Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century explores the sculptural traditions of the Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms from the early 5th to the close of the 8th century in mainland and insular Southeast Asia.

This landmark exhibition will be the first to present the religious art produced by a series of newly emerged kingdoms in the region, whose archaeological footprints lay the foundations for the political map of Southeast Asia today.

“Exhibitions that provide this level of exposure to previously unfamiliar material of such significance come along very rarely,” said Thomas P Campbell, director and CEO at the Metropolitan Museum. “The majority of the important and breathtakingly beautiful works in Lost Kingdoms have never before travelled outside their source countries. We are especially honored that the government of Myanmar has signed its first-ever international loan agreement in order to lend their national treasures to this exhibition.”

Thierry Ollivier

Thierry Ollivier

Recent excavations and field research have made it possible to redefine the cultural parameters of early Southeast Asia, a region that created some of the most powerful and evocative sculpture of the Hindu-Buddhist world in the first millennium. The results are presented in both the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue.

Among the masterpieces in the exhibition are a 6th-century Buddha Offering Protection; a spectacular Krishna Holding Mt. Govardhana from the hill shrine of Phnom Da in Southern Cambodia; a late 7th-century Avalokiteshvara discovered in the Mekong delta of Vietnam in the 1920s, which is arguably the most beautiful image of the Buddhist embodiment of compassion in Southeast Asia; Devi, Shiva’s Consort Uma, a piece of startling naturalism that possibly embodies a portrait of a deceased Khmer queen of the first half of the 7th century, an ascetic Ganesha from the 8th-century religious sanctuary of My Son in central Vietnam; and a Dvaravati kingdom terracotta sculpture of the 7th century, Head of Meditating Buddha, a sublime representation of Buddhist meditation.

Lost Kingdoms is organized thematically into seven sections representing the major narratives that have shaped the region’s distinct cultural identities.

Imports features rare surviving examples of exotic objects from early India and further West that were discovered in Southeast Asia. These objects served as models for local artists employed in the service of the ‘new faiths’ of Hinduism and Buddhism.

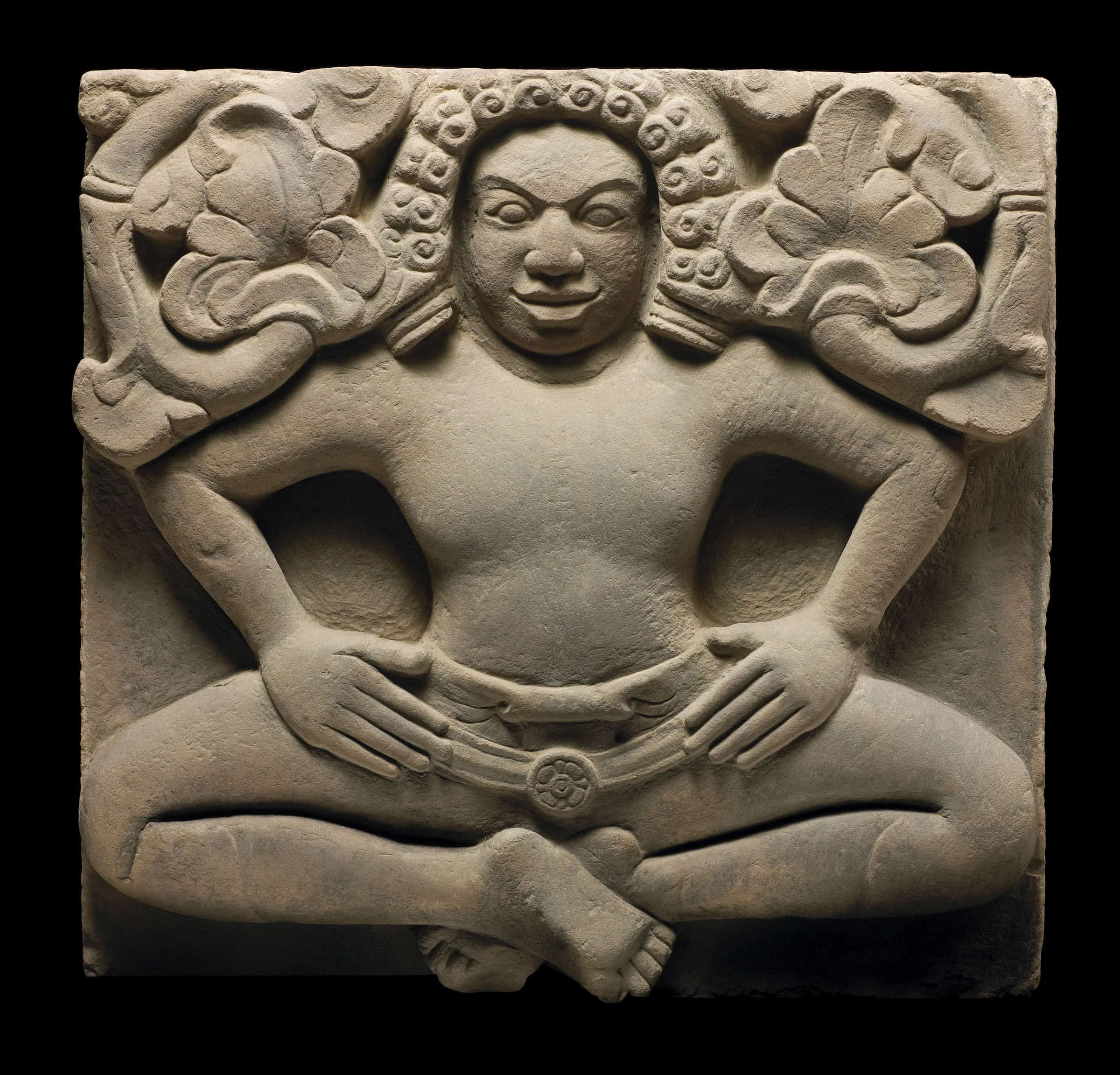

Nature Cults presents objects demonstrating the persistence of nature-cults in Southeast Asia well into the Hindu-Buddhist period. The adoption of the Indic religions in the region was highly successful due largely to the receptivity of these pre-existing animistic belief systems.

Arrival of Buddhism explores the early expressions of the Buddhist faith in Southeast Asia. Central to this section will be precious objects recovered from a unique relic chamber discovered in the ancient walled Pyu city of Sri Ksetra, in central Myanmar, datable to the 5th to 6th century. This section also features a series of life-size Buddha images – from Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam – showing the universality of the Buddha’s message expressed in distinctive regional styles.

Vishnu and his Avatars illustrates the responsiveness of the region’s earliest-known rulers to Hinduism, as exemplified by their embracing of Vishnu as an ideal model of divine kingship. Rulers dedicated numerous shrines to Vishnu and a selection of the large-scale sculptures from such sanctuaries will be on view.

Siva’s World presents the cult of Siva and his family, including Parvati, Ganesha, and Skanda, and the cult of the Shiva-linga as divine protector. A central focus is the work of Khmer artists, who generated new forms of expressing Shiva’s identity not seen in India.

State Art explores Buddhist art as an expression of state identity. It focuses on the patronage of the Mon rulers of the Dvaravati kingdom of central Thailand. This section includes some of the most monumental works in the exhibition: several large-scale sandstone standing Buddhas, sacred wheels of the Buddha’s Law, and steles depicting stories from the present and past lives of the Buddha.

The final section, Savior Cults, is dedicated to the cult of the Bodhisattva, the Buddhist saviors and their dissemination throughout Southeast Asia. The expression of this tradition outlived its source in India, and its independent evolution is traced through major cult images that share an iconographic language, yet exhibit strong regional styles. The late 8th century also marked the beginning of a new age of Asian internationalism, in which the kingdoms of the region were linked through thriving international trade networks. Religious ideas, rituals, and imagery circulated quickly, unifying the region and integrating it into greater Asia as never before. This was reflected most strongly in the newly emerging, shared visual language in the service of Mahayana Buddhism.

The exhibition runs until July 27.