I don’t know about you, but in lieu of travel, I’ve been spending a lot of my free time reading. My favourite literature takes me far away from the current political climate and COVID-19 news back to days when we could roam freely. (What a privilege that was!)

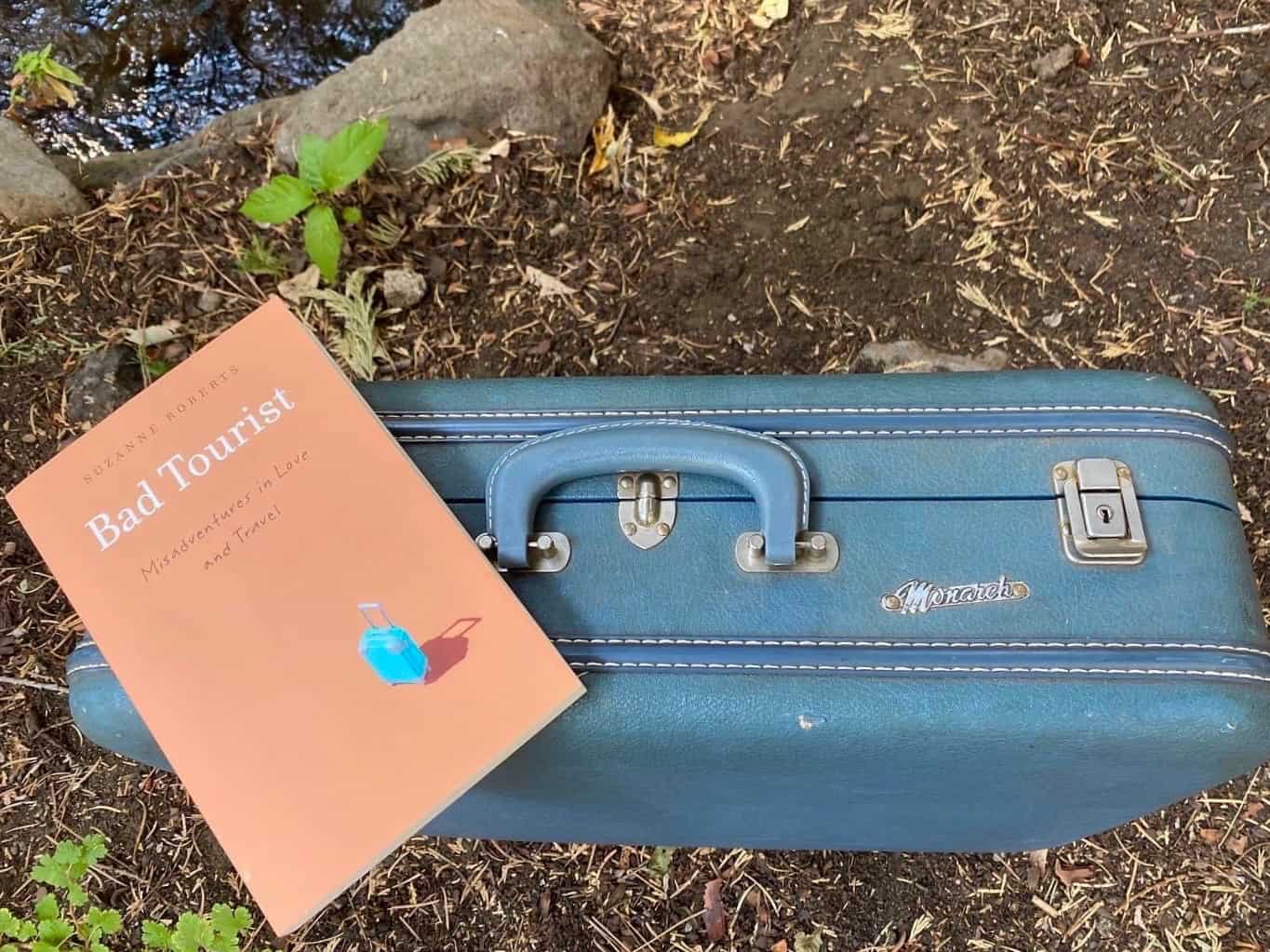

One of the best travel memoirs in essays I’ve read recently is Bad Tourist: Misadventures in Love and Travel by Suzanne Roberts. If the title doesn’t draw you in, the well-written prose will.

I brought the collection of essays to the beach (at home, in Vancouver) for a little escapism from our currently grounded experience. I was transported to Costa Rica, Peru, India and Scotland. The thematically organized stories—mimicking a Lonely Planet travel guidebook—probed me to think more about myself and the world, as every good travel book should.

I laughed out loud, grimaced and nearly cried while reading Bad Tourist. I found myself wondering about Suzanne herself—I’m always curious “why” we desire to rove—so I connected with the author virtually to discuss what propels her to travel, how she’s been getting through the lockdown and what it means to be a “bad tourist.”

Note: Conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

What does it mean to be a “bad tourist”?

Bad tourist is sort of a double-negative because when we think of the word “tourist,” it usually has negative connotations—so it’s a little ironic. I think we’re all good tourists and bad tourists at some point—in the same day, maybe in the same hour. I’ve travelled long enough where I’ve heard lots of conversations about “traveller versus tourist,” and I think to the locals it’s the same thing—whether you have a backpack on and are riding on the local transportation or are staying at a resort. I wanted to recognize the idea that travel has dangerous roots in imperialism and colonialism. We need to keep in mind the cultural blind spots we have that might be funny but are also serious.

How can readers avoid being "bad tourists"? Or is that even something to aspire to?

I definitely think we can all be better bad tourists by doing our research before we go. Is that ecolodge really an ecolodge? And with research we can stay and eat in locally owned places to help the local economy (rather than giving money to foreign investors). Also, learn a second language so we can communicate with locals in a more authentic way, rather than just the capitalistic exchanges. Stay in one place longer, and if possible be a guest versus a tourist or traveller: try to do something meaningful like teaching (though beware of “volunteer” opportunities that don’t really help and just make the traveller feel better about herself, feeding the white savior complex).

Why did you write this book?

There’s a lot of great books about travel by women. I’m adding my uniquely feminine and feminist perspective to this canon of mostly white male explorers. The more diverse voices we can get out there, the better. We need a lot more women of colour writing travel.

Gayle Brandeis

Gayle Brandeis

My favourite essay from your book is "Bellagio People." What’s yours?

It varies day to day, honestly. I feel connected to “My Mother Is My Wingman.” That essay is going to be in Best Women Travel Writing, which is coming out in November. “Three Hours to Burn a Body” is also an essay I’ve been working on for so long—since 2007—it was first a poem, then I felt like I had a lot more to say. I like the way that came out. Also, “Sassy in Burning Man,” which is one of the newest essays in the collection. That’s when my narrator finally comes into her own and says, “no, I’m not putting up with the things men do.”

Why do you travel?

My first inclination is to say, “Why wouldn’t I travel?” I think it’s really important for us to see the way that other human beings live on the opposite end of the planet. It connects us to our shared humanity. That’s the big answer.

The more personal answer is that I feel like travel extends my life. . . it makes my life feel longer. When we’re kids, the days are so long, because our synapses are making all these different connections, and it makes time stretch. When we’re adults, and as we get older, the years seem to go by faster and it’s because we’re doing the same thing over and over. We aren’t making any new connections in our brains. In a very real way, we can extend our lives by going new places, seeing new things and having new experiences.

What advice would you give solo female travellers?

Don’t be afraid. My worst fear was getting sick alone, and I got really sick in a hostel in Peru—I thought I was going to die. And I didn’t die. Those are the things that make you more confident and feel stronger. Because the thing you’re most afraid of happened, and you’re fine.

Relying on other women in the destination and your network of women around the world is going to help you. If you need help, you can ask a woman for directions. Once we can do so safely, just go. It’s sometimes scarier at home.

As a traveller, how (and what) have you been doing during the COVID-19 pandemic?

I took up mountain biking! [Laughs and shows off arm cast from recent fall and break]. Part of my identity is being a traveller, but being a traveller is a state of mind. I can go for a hike behind my house and be a traveller and see new things. I don’t feel like I’ve lost that part of myself.

We have to force ourselves to do new things and open up to other ways to be creative. I’m still travelling—my husband and I bought a van. I do feel a little bit trapped, but I have a British passport, so we’ve talked about going to Scotland for the next four years, depending on how the election goes.

Candice Vivien

Candice Vivien

What’s next?

In the last five years, my husband and I have had a ton of losses. I write to make sense of the world. So right now, I’m working on a book of essays that focus on grief, called The Grief Scale, which will be published in 2022 by Nebraska. I’m finding the connection between grief and travel an interesting thing I hadn’t thought about much. I organized it around the grief scale—denial, bargaining, all that—and it’s meant to be ironic. . . an anti-guidebook to grief.