By Peg Fong

The landscape of Scotland has inspired writers for centuries giving rise to some of fiction's most memorable characters from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to Sherlock Holmes to a boy wizard named Harry Potter.

In the Scottish Highlands, look and listen for the sounds of rolling trains. For over a century, the railway line connecting the West Highlands of Scotland to its largest city of Glasgow and then onwards to its capital of Edinburgh was a crucial, yet under-used transportation link.

So remote is this section of the country that there was talk a few years ago of closing down the Glenfinnan station.

But Glenfinnan’s fortunes turned when a bespectacled boy named Harry Potter boarded the Hogwarts Express and took the same curve over the viaduct at the start of each school term to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

Today, fans of the Harry Potter series by Edinburgh-based superstar author J.K. Rowling take the steam train to ride across the rail line that the movies depict in scenes such as the flying car sequence and the Hogwarts Express crossing over the viaduct.

Peg FongWhen the train conductor announces near the end of the three-hour journey from Glasgow that the viaduct made famous by Harry Potter is approaching, passengers rush with their cameras to get a glimpse.

Peg FongWhen the train conductor announces near the end of the three-hour journey from Glasgow that the viaduct made famous by Harry Potter is approaching, passengers rush with their cameras to get a glimpse.

One of the passengers on the train, seven-year-old Louis Clift, visiting from England, with his parents was wide-eyed as he followed in the path of his literary heroes. In a cape proclaiming that he is a proud Hogwarts Alumni, Clift carried a pretend wand; his eyeglasses were real, and his imagination was full of the wisdom of Dumbledore and the brave acts of Harry Potter.

“They’re just really good stories,” he says. “Dumbledore is my favourite.”

The village of Glenfinnan itself does little to market its connection to Harry Potter even though a recent poll ranked Hogwarts as the 36th best Scottish educational establishment after it was listed for fun and then voted on by public.

“Glenfinnan’s been here for a long time before Harry Potter and will continue to be here a long time after the movies,” says Duncan Gibson, resident manager of the stone mansion Glenfinnan House Glenfinnan House, one of the country’s oldest inns, first built between 1752 and 1755.

But while Scotland's lush and verdant countryside may have inspired its writers, it is in their capital city of Edinburgh where every street and corner seems to have a literary connection.

The 61-metre high Sir Walter Scott monument, once described by Bill Bryson as a “gothic rocket ship” looks oily and grimy from the outside because of the type of sandstone it is built from, but a climb up the 287 steps is well worth it for the panoramic views of central Edinburgh.

Peg FongWaverley Station, the only rail station in the world named after a novel, is a vibrant hub of the city just a short walk to two of Edinburgh’s premier hotels. The Apex Waterloo, with its ultra-modern rooms and elegant stone facade, was a favourite of Charles Dickens who stayed there while writing Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities. Across the street, the luxurious Balmoral Hotel with its high-ceiling foyer and soft, golden, welcoming lights was the place where J.K. Rowling holed up to finish the last chapters of the final book in the Harry Potter series.

Peg FongWaverley Station, the only rail station in the world named after a novel, is a vibrant hub of the city just a short walk to two of Edinburgh’s premier hotels. The Apex Waterloo, with its ultra-modern rooms and elegant stone facade, was a favourite of Charles Dickens who stayed there while writing Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities. Across the street, the luxurious Balmoral Hotel with its high-ceiling foyer and soft, golden, welcoming lights was the place where J.K. Rowling holed up to finish the last chapters of the final book in the Harry Potter series.

“We are stuffed with literature from every part of our country and especially here in Edinburgh,” says Anna Burkey, community coordinator with UNESCO City of Literature. “Walter Scott created the romantic image of Scotland as a place of tartan and heather and rollings hills, bagpipes and from then on, there’s been the identity of this country.”

Edinburgh became UNESCO’s first City of Literature in 2004 after four local book lovers thought the city and the entire country should take on responsibility for the future development of a literature culture that has developed because of the country’s history.

It’s not just authors and publishers who reap the rewards of living in a city full of literary connections but book lovers are themselves celebrated. A walk through the city centre’s St. Andrew’s Square is a step into surroundings where the love of words is proudly heralded. Colourful displays have been fitted in the windows with quotes about the city from famous literary figures.

“Who indeed that has once seen Edinburgh, but must see it again in dreams waking or sleeping?” Charlotte Bronte wrote in a letter. Others were more jaded. “It is quite lovely – bits of it,” concluded Oscar Wilde.

The National Library of Scotland, with its 14 million books and origins dating back to 1689, houses the John Murray Archives, a collection of two centuries of the firm’s publishing history. The tradition of publishing continues and thrives today in Scotland where publishing brings as much money into Scotland as the cashmere industry and almost as much as the salmon trade.

At the library, visitors can find letters from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a medical student at the Royal College in Edinburgh who fashioned his famous detective after one of his professors, and the rain-stained African field notes made by David Livingtone of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume” fame.

The thriving Literature Quarter along Edinburgh’s famed Royal Mile houses the Scottish Storytelling Centre with exhibitions and events that highlight the love of sharing stories and the Scottish Poetry Library.

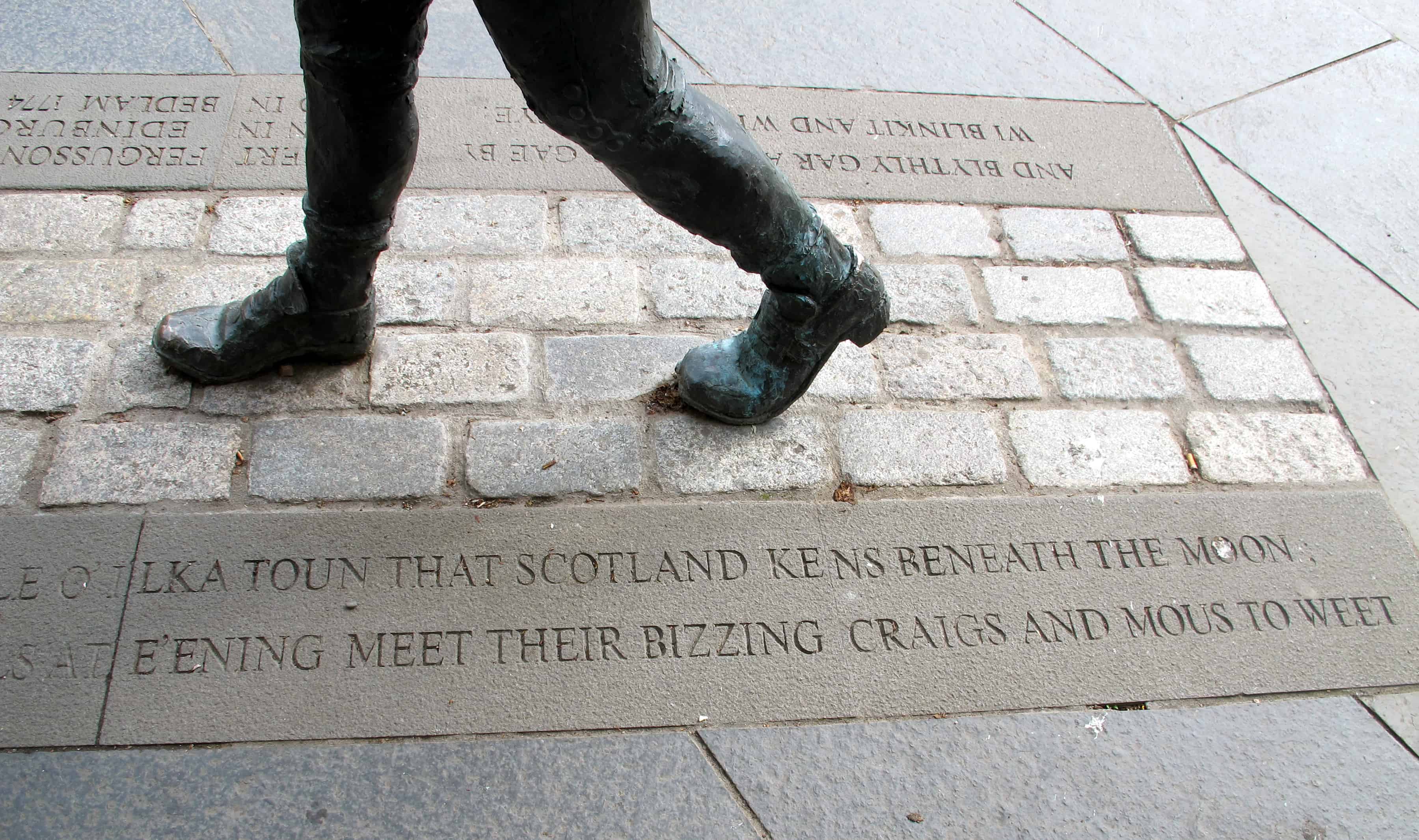

From the Royal Mile, take a short walk down Canongate, which was once its own separate district with a still-visible ancient toll booth. Canongate Kirkyard, the cemetery, is watched over at the entrance by a statue of Robert Fergusson, a Scottish poet so admired by fellow writers that Robert Burns erected a gravestone for his unmarked grave and Robert Louis Stevenson paid for repairs to the headstone after it had been damaged in an accident.

Peg Fong

Peg Fong

The traditional and quaint tea-rooms much are still thriving in Edinburgh and at Clarinda’s Tea Room, named after one of Robert Burns’ muses, the pastries are plentiful and charmingly displayed on a tea cart in the flowered wall-papered room filled with porcelain knick knacks. Scones with cream and tea cost 3.30 pounds. The homey atmosphere was evident by this exchange witnessed during a visit. “Is the ginger bread good here?” a passerby asked, sticking his head into the tea room. “Reasonably,” replied one of the patrons. “Our scones are better,” one of the servers agreed honestly.

The Writers Museum located in a square off the Royal Mile is dedicated to three of Scotland’s most famous writers – Robert Burns, who lived in a building facing the square, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson. These writers had eclectic and varied lives, as their belongings amply show, from Scott’s rocking horse to Stevenson’s ring, given to him by a Samoan chief engraved with the name Tusitala, meaning “teller of tales.”

Crammed with pictures, etchings, busts and memorabilia and of course samples of their writings, the museum is a gentle haven from the frenetic pace of the Royal Mile beyond the arched entranceway to the square. Here, the words of writers, carved in stone, are loud enough to be heard.