Jeff Nesanelis

Jeff Nesanelis

The beat-up Chevy truck has been this way before. At least that’s my take from the groaning of the engine, the cracks in the seating, and the upholstered panel missing from the inside passenger side. We’re bumping along just outside the small community of Page in northern Arizona, heading into the heart of Navajo Nation for a day of hiking in the mysterious depths of slot canyons.

Getting there is an excruciatingly slow, teeth-jarring, potholed drive from Page. One-way, it takes almost an hour to cover 26 kilometres across wide-open desert, punctuated by the low puffs of green sagebrush and the occasional locked gate blocking the way.

Canyons – large and small – are a part of the Southwest landscape. The narrow slot canyons have an intimacy that is lost in the grander canyons. They are deep, swirling fissures that began eons ago as hairline cracks in the sandstone blocks that largely make up the sweeping Colorado Plateau. Slots are rare and elusive; curvaceous masterpieces of eddying and twisting red sandstone, carved by the forces of wind and water. The surface appears fluid but it is solid rock.

We’re headed for the mysterious Canyon X, a spot the guides like to protect from the onslaught of tourists that have overrun its better-known neighbour, Antelope Canyon, the most photographed and visited slot canyon in the American Southwest. Canyon X was named by a member of the Navajo Nation whose aunt owns the grazing rights to the land – its namesake is the mysterious and haunting television show, The X-Files.

From the air, slot canyons appear as a slash on the landscape; a calligraphy mark inked onto the expanse of the plateau. Water collects and moves through the cracks, rushing through the cut in the rock, and even the slightest irregularity causes the water to swirl and eventually carve a round hollow in the sandstone. The slot is a series of these swirling, twisting hollows, connected by narrow passageways of varying length. They are extremely narrow cuts into steep-walled sandstone; sometimes just a metre wide at the top and hundreds of metres high from the rim to the natural, sand floor.

It takes a bit of scrambling to make the hike down into the start of Canyon X. Along the way, wildflowers cling in spots where it seems no growth was ever meant to survive. The canyon is also home to bobcats, coyotes, porcupines and the occasional rattlesnake.

Through daylight hours, the beams of light filter in from above and bounce from one reddish wall to the next, creating a kaleidoscope of colours and patterns enhanced by the shadows, arches and curls of the contoured stone. The way the light bounces and the colours shift makes slot canyons popular outings for photographers.

Across Arizona there are spots off the beaten path where it really is best to just take your finger off the map, fold it up, put it away, and sit back to enjoy the ride. Come with us to explore some of Arizona’s unique landscapes.

Metropolitan Tucson CVB

Metropolitan Tucson CVB

- If not the largest canyon in the world, the Grand Canyon is certainly the most famous. It certainly caught the attention of adventurer and mapmaker John Wesley Powell, the first explorer to voyage through the canyon on the Colorado River in a stout wooden boat on his landmark 1869 expedition. Modern day ecotravellers can explore the “layer-cake geology” on foot, by multi-day raft tours and on donkey excursions. For the adventurous, a trek from the rim to the canyon floor crosses four different life zones. www.nps.gov/grca/

- Chiricahua National Monument in southeast Arizona is known as “a wonderland of rocks,” because of the balanced rocks, columns, spires and pinnacles remaining from the violent geological activity that dominated the area for millions of years. The region is popular for camping and hiking. www.nps.gov/chir/

- There is no better introduction to the Sonoran Desert than through the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum at Tucson. It’s a world-renowned zoo, natural history museum and botanical garden, with exhibits of more than 300 animal species and 1,200 kinds of plants. Some of the more unique features are the behind-the-scenes animal keeper tours and the raptor free-flight demonstrations. After learning about what makes this desert environment unique, you can step outside and hike the trails at the Saguaro National Park. www.desertmuseum.org

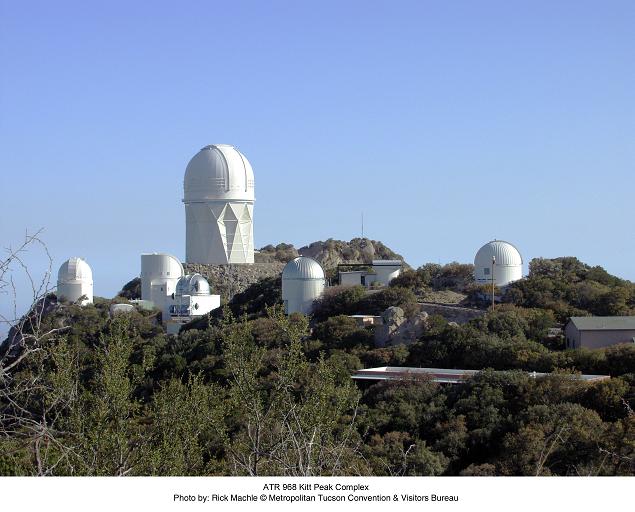

- The clear skies and low pollution make Arizona a hotspot for astronomy. Observatories are found at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Mt. Graham in the Coronado National Forest. Mt. Lemmon and the Kitt Peak National Observatory, both outside Tucson. Several resorts and guided businesses offer stargazing programs. In the Sedona area, Sedona Star Gazing offers customized tours of the night sky led by professional astronomers. www.eveningskytours.com

- Over 225 million years ago, the grasslands of central Arizona were more like a humid, tropical soup. Dinosaurs and giant reptiles roamed the forests of huge trees. The region was uplifted, the climate changed and the landscape became the high, dry grasslands we see today. The giant logs from fallen trees – once buried in silica-laden groundwater – have been preserved as colourful petrified wood. The park can be explored along a 45-km drive (the best petrified wood is in the southern part of the park) or along several short trails. Warning: It is illegal to remove any of the petrified wood. Mysteriously bad luck follows those who do! www.nps.gov/pefo

- Almost a thousand years ago, the volcano at Sunset Crater erupted with lava flows and burning cinders, raining down on the pithouses of the people who farmed there at the time. The lava flows destroyed all living things in their paths. At Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument you can walk the two-kilometre Lava Flow Trail at the base of the volcano. It crosses through an eerie landscape of hardened black cinder and lava. www.nps.gov/sucr

- Just north of Tucson, the University of Arizona Biosphere 2 has recreated a western hemisphere rainforest under an enormous roof of glass. Recently named one of the 50 must see Wonders of the World by Time Life Books, the pathway inside the Biosphere leads through a simulated Brazilian rainforest with over 150 species of plants. www.b2science.org